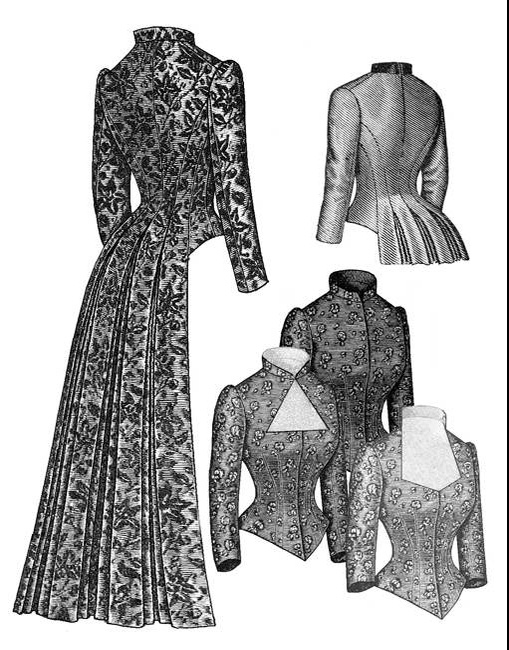

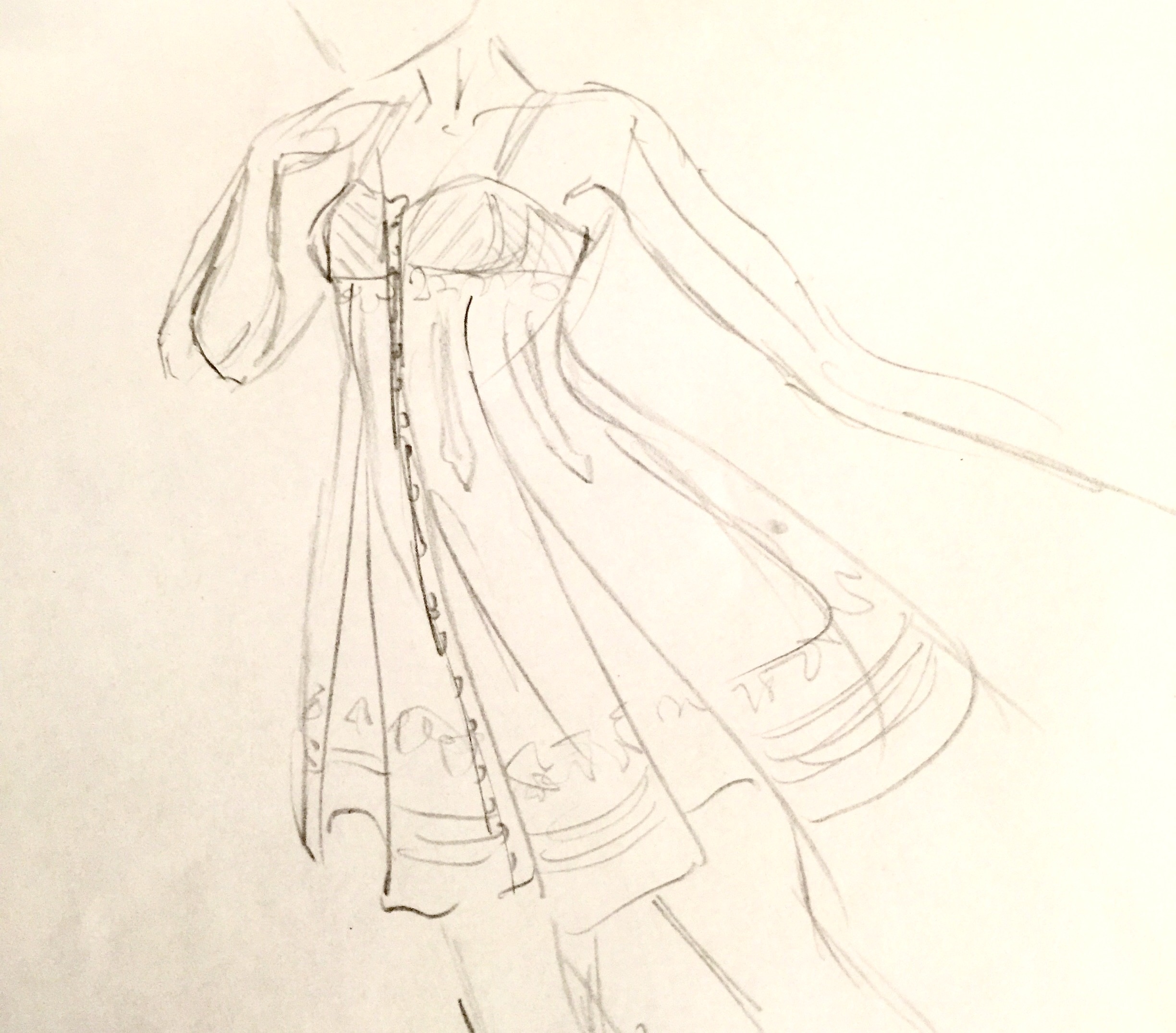

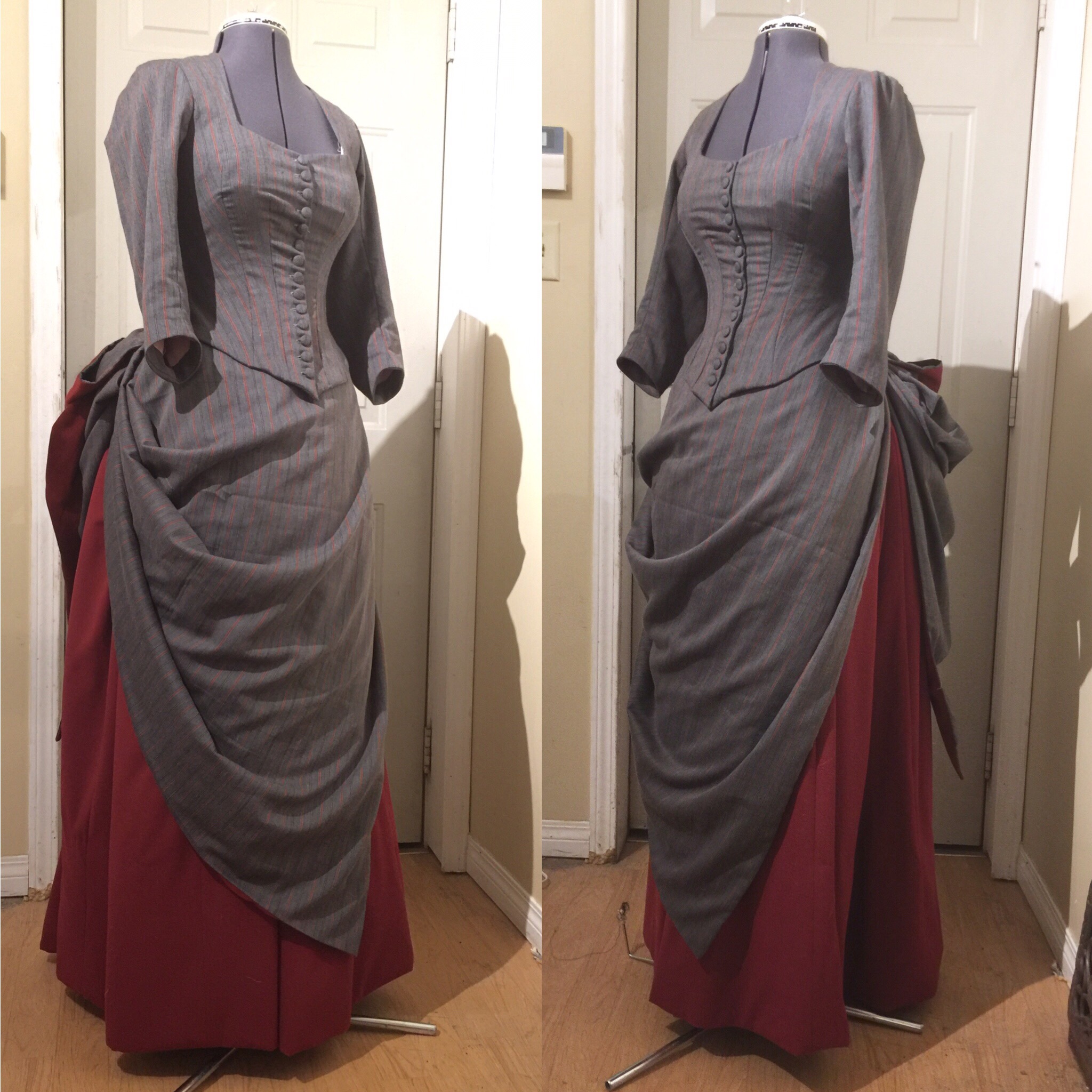

This is part 2 about my “Victorian sundress” project. I drew on two main inspirations for the skirt. One was this blog post from the Fashionable Past, about an extant and very lightweight summer dress (unlined skirt!!!), and the other was this pattern from Etsy, the “Étamine Dress.”

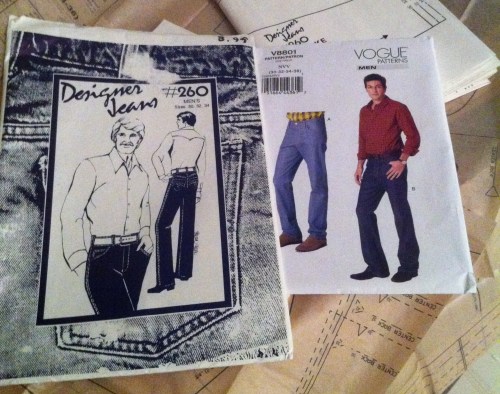

It’s one of those “unimproved” ones based on an original from Harper’s Bazar. No grading, no additional instructions. I didn’t particularly care about the bodice, having just muslined my own, but after a few mind-boggling attempts to work out all that layered pleating on my own based just on the illustration, I bought the pattern.

As I had feared, the pattern piece was LARGELY a rectangle. with a very slight curve at one end. So I was basically paying for the marked pleat points, and about two lines of instructions. Ah well. (Actually the terse instructions were really helpful in clarifying the dizzying array of layers on the dress in the image, even if I wasn’t likely to have enough fabric for all of them. )

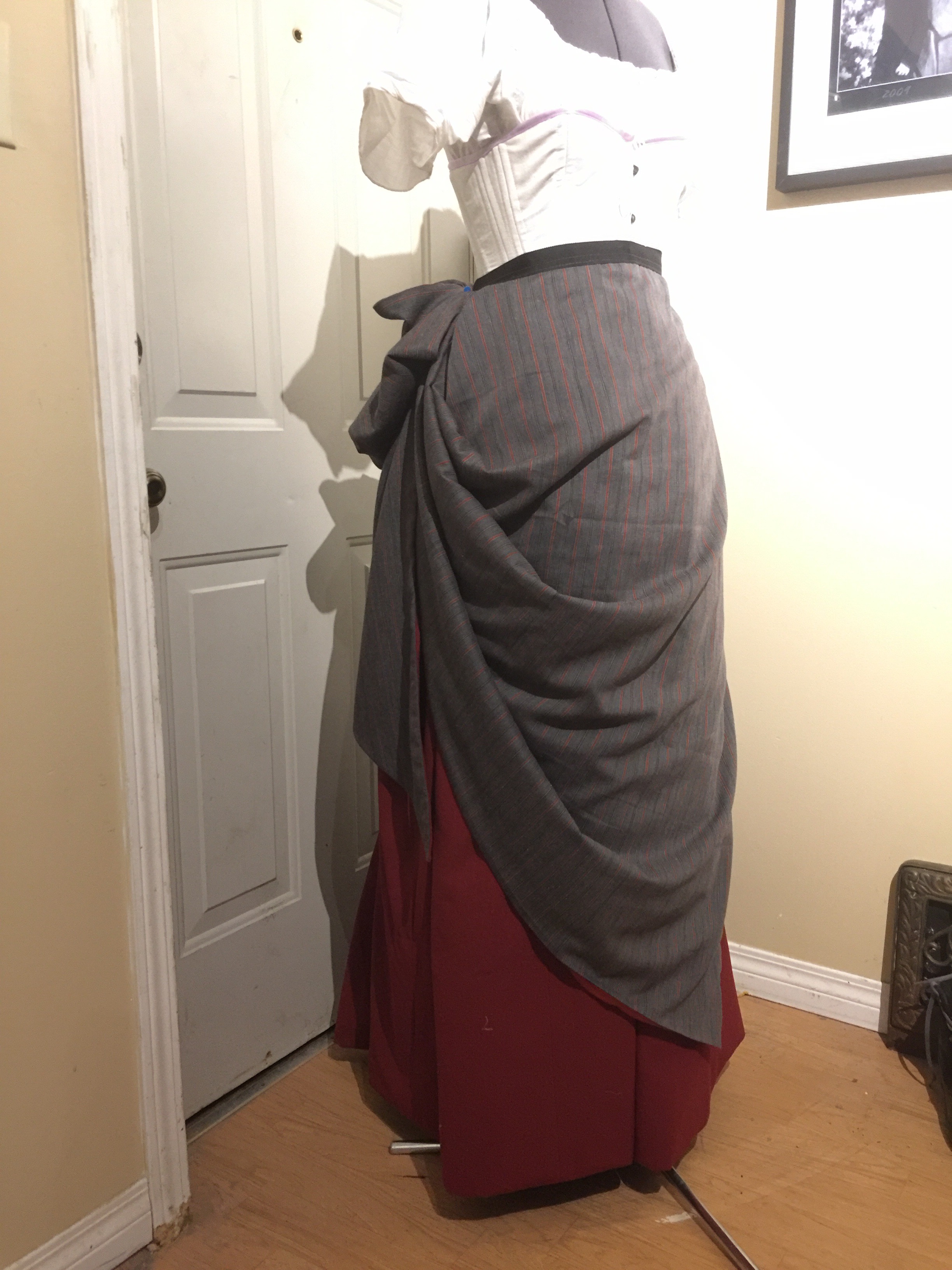

The Étamine pattern skirt, as written, contains four layers. From the inside out:

- The foundation skirt,

- A “tablier front” pleated just across the front, visible in the slit between all the other layers,

- The “straight breadths”, a straight, pleated layer (probably meant to be applied to the foundation skirt?), and then finally

- The swagged outer layer.

The pattern actually includes a piece only for the final, outer layer—which was the main reason I bought the pattern, and which, it turns out, is also basically a rectangle, curving only very slightly on the top front. (And in hindsight that curve probably only exists to accommodate attaching this layer to the bodice, as per the instructions, which wasn’t my plan until I realized that)

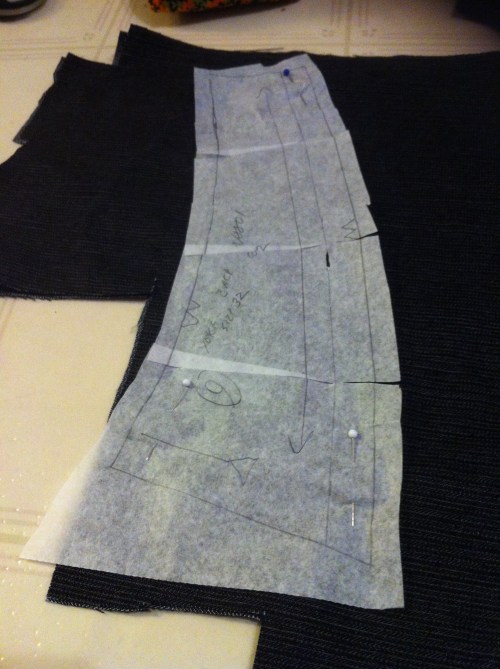

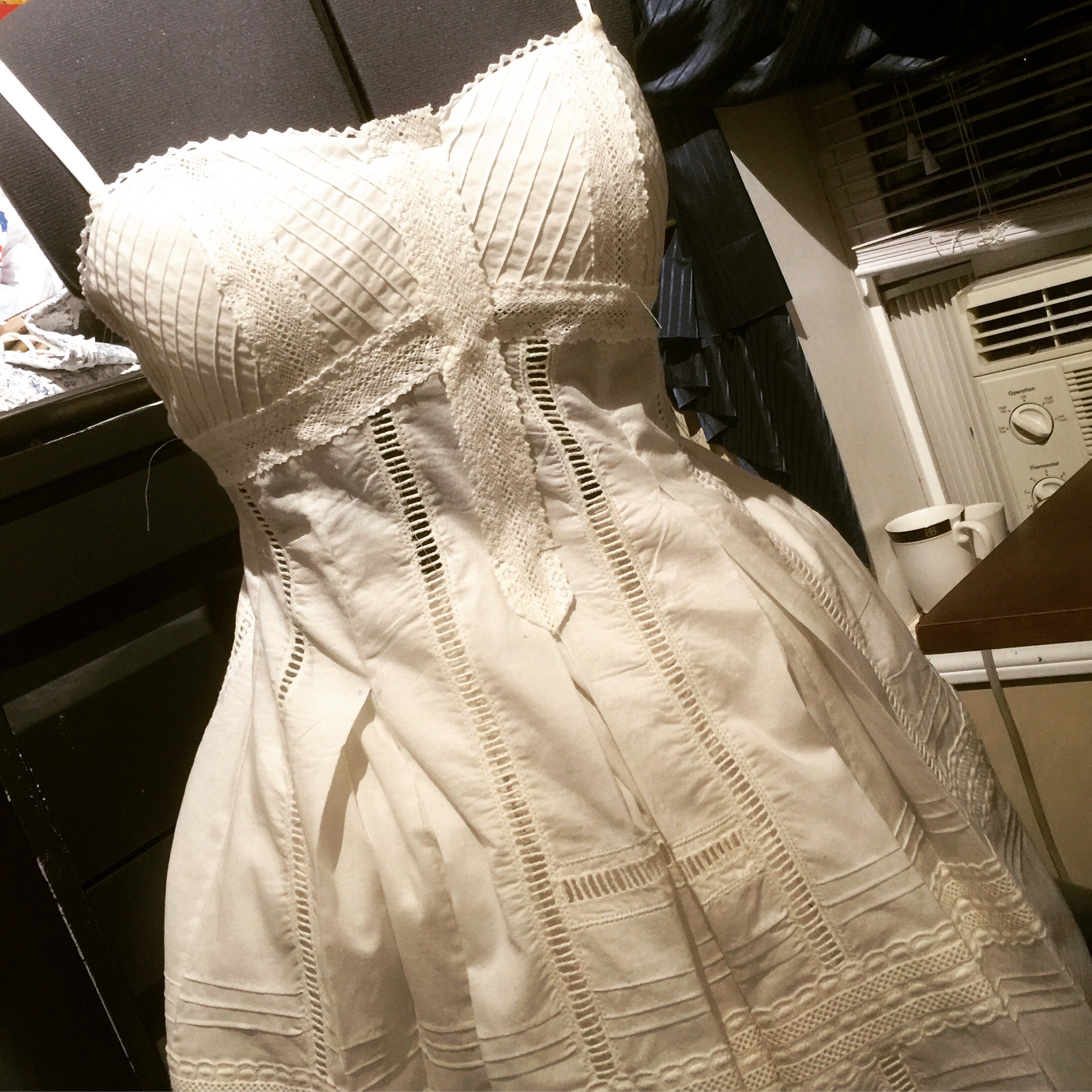

But I’m getting ahead of myself. First I needed to construct the foundation skirt.

Based on both my desire for a maximally light weight dress and this blog post from The Fashionable Past about recreating an extant, and remarkably lightweight, dress in her possession, I decided to throw propriety to the wind and make an unlined foundation skirt. The complete invisibility of the foundation skirt in the Etamine dress illustration did little to dissuade me from this course, and actually, if the “straight breadths” and “tablier front” layers were mounted to the skirt as I suspect the pattern intended, it might very well have been a single layer foundation skirt that was intended.

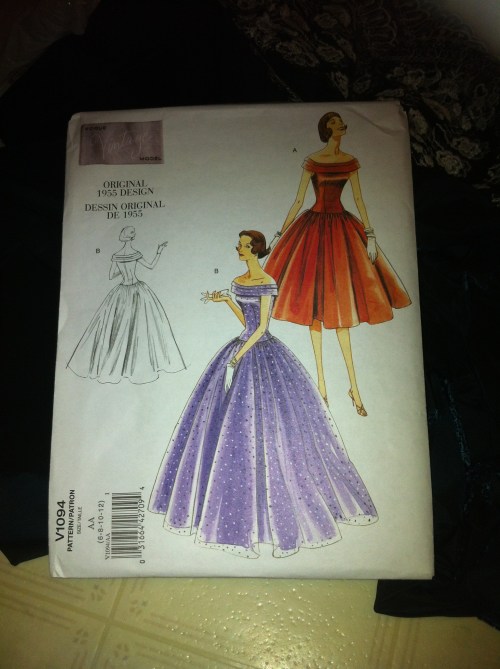

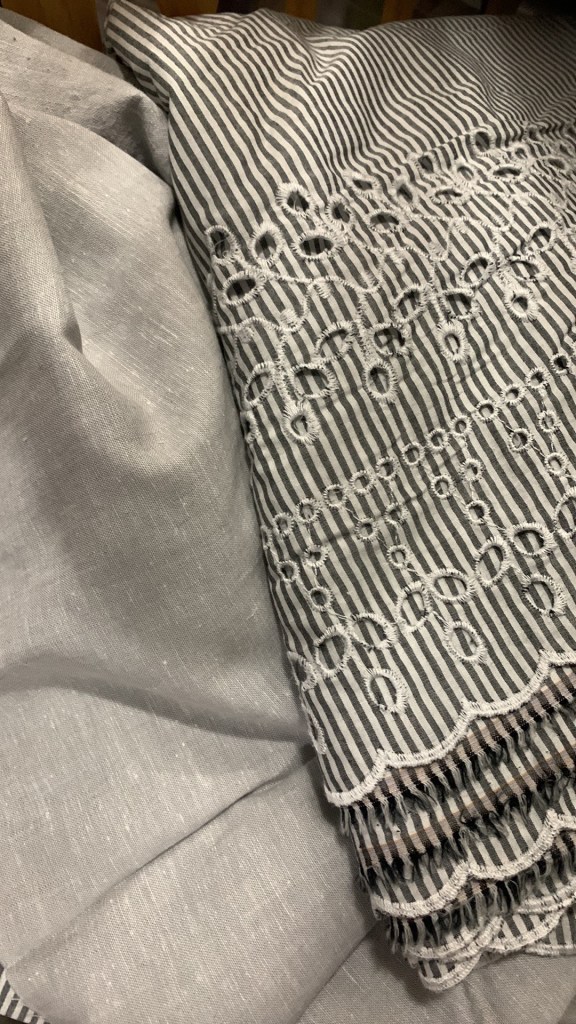

My fabric was about three metres of this grey cotton-linen blend, a long-stashed remnant from this Vintage Vogue dress. The colour coordinated well with my grey striped border embroidery, although if it proved invisible in the final product it wouldn’t matter. It’s not a particularly historical-looking fabric, but it is yummy.

I constructed the foundation skirt in a low-waste gored manner similar to this skirt draft from my 1882 book and this 1903 petticoat draft, although slightly modified to take advantage of my wide modern fabric. I cut both front and side gores from a single length, and then used a further full width to make my back panels. In hindsight the front gore is too flared for this skirt style, making the seams run somewhat diagonally down the skirt. I should’ve cut it narrower at the hem edge, and then had a bit more fullness to pleat in to the back waist. But, see the part about how it’s basically going to be invisible, I’m not too bothered.

For the closure, I made a pleat-placket in the middle of the back breadth, using the same slash method I did for my first petticoat, which according to past Tanit came from Plain Sewing and Amateur Dressmaking (published in 1887). This part was entirely hand sewn. It’s completely covered in the final dress, but somehow was just fun to do.

The Étamine pattern, by the way, barely even mentions the foundation skirt layer in its terse instructions, except to say it has a four-inch box pleating of the fashion fabric at the hem. They were obviously assuming their reader either had a basic foundation skirt pattern they liked, or would just draft their own like I did.

Because I like the look, I decided to try out stacked pleating at the centre back, covering my placket pleat. I didn’t fuss over it too much. The single layer of fabric definitely made this a less bulky feature than it might have been.

My hem is just a very basic machine hem, again based on the Fashionable Past example, although a little narrower.

I also made a pocket, again very much following the same method I’ve used in the past. However, it somehow turned out too small. So I may need to open up the bottom of it and patch on some more. I also initially sewed it in upside down, because you’re never too experienced to make mistakes.

Now, the skirt came out relatively short. This is partly because of fabric limitations and partly because all my Victorian skirts ever have been too long, at least for day wear. I did not want that for this skirt—but I definitely needed to shorten my petticoats.

I did this by the very inelegant method of adding a 1” tuck just above the bottom ruffles. Because the front and sides are gored (i.e., wider at the bottom than the top) this means that the underside of the tuck needs to be eased to fit. The period manuals talk about basting a gathering stitch along that line and easing it in. I just pressed and hoped. It mostly worked out better than expected, though there are one or two bad spots.

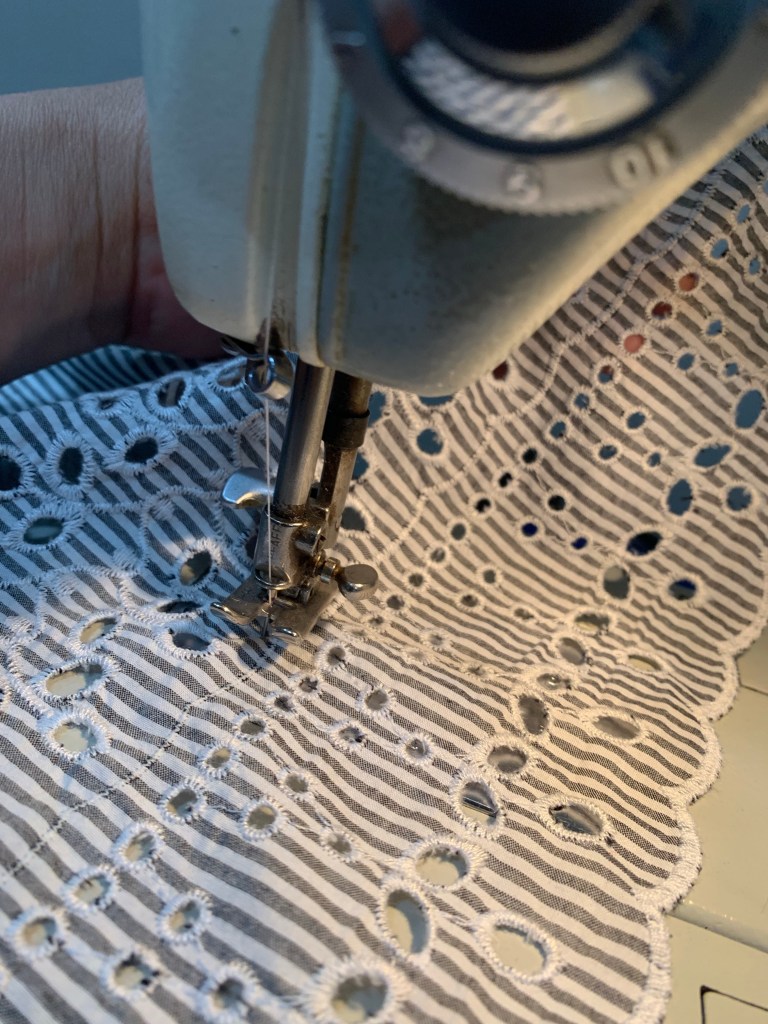

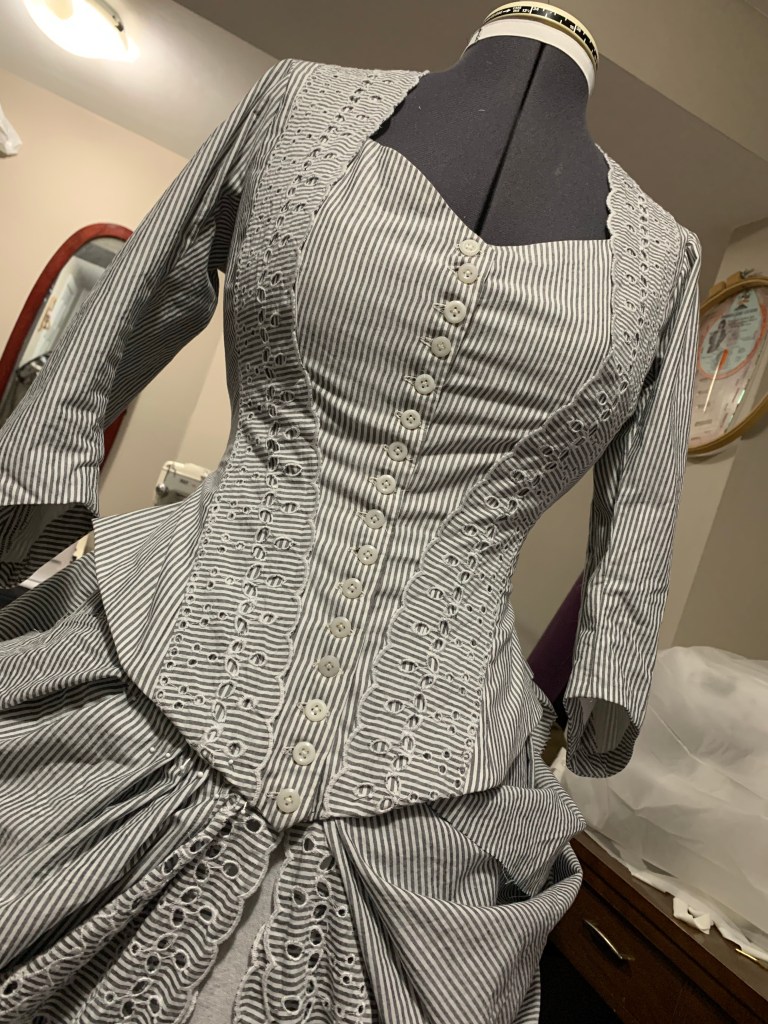

With considerable fussing and measuring, I eventually determined that I did have enough of the border embroidery to do at least the upper two layers of overskirt, although not the tablier front layer. I was content to have my foundation skirt show a tiny bit though. I had enough extra eyelet trim from the making of the bodice to add a vertical piece to the centre fronts of the topmost layer.

There was, however, nothing left for the longer fronts of the middle layer, what the pattern termed “straight breadths.” Never mind any excess for trimming the bodice. I considered for a long, painful while, but I knew what I had to do: make more edging.

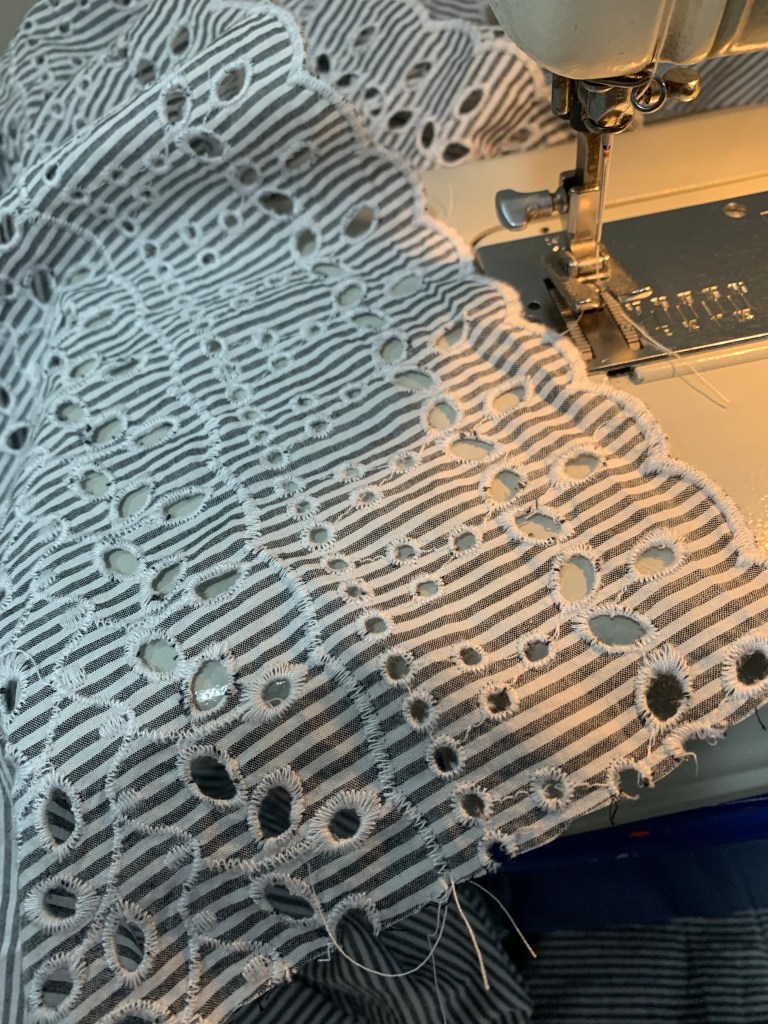

You see, as it happened the existing border embroidery was arranged kind of in two rows with a small space between them. This made it possible, with enough patience, to add a scalloped zig-zag in the space between that I could then cut along, instantly doubling the amount of eyelet edge I had available.

I thought the best machine I had for the task would be the Pfaff 360, as its embroidery stitches are customizable to length. However, it has a dodgy tension and hadn’t been out of the carrying case in, um, years.

Eventually, I managed to nerve myself up, pull the Pfaff out, and get to work.

The tension was actually being fairly well behaved, but the embroidery stitches didn’t seem to be engaging, or at least only very randomly. I eventually traced the issue to a series of little levers under the main cover of the machine that are supposed to drop down into slots depending on which stitch option is selected, which were not dropping without manual assistance. So, eventually, I was able to get it to do a scallop the length that I wanted—but there didn’t seem to be a width adjustment available for the scallop setting, and I could only make it do a very narrow zig-zag. I think this is a limitation of the machine, since it has a fairly narrow total stitch width; in the end I went over the automatic scallop with a wider zig-zag freehand, and aside from the tension being a little too low (I had turned it down as that tends to work best for machine embroidery, and it looked great on top and didn’t pucker up the fabric, but it is quite loopy on the back side.) It’s not indistinguishable from the original, but it won’t be noticeable, and I desperately needed that extra length of edging.

I think cutting the strip off the bottom may actually have taken longer than embroidering it. But eventually it was done. Then I remembered I also needed to add three 1” tucks to the “flat breadths” panel before I pieced on the edging at the short ends.

But eventually I got it done. It was easier than the upper layer since the mitered corner was narrower. The removed edging isn’t the same as the remaining piece, but at least their width is similar.

Based on the terse instructions, I actually think the “flat breadths” layer was supposed to be attached directly to the foundation skirt, attaching partway down, even though the illustration doesn’t exactly fit with this idea. But I didn’t want to do it that way, mainly because I feel like I might want to wear the foundation skirt alone for other things. As a result my “straight breadths” are pleated into a twill tape waistband and hike up a bit in the back. If I really wanted I could probably come up with a bit of an upper skirt to mount them to, but at the moment I’m not sure I’ll bother.

At last I could truly play with the upper layer. I was grateful to the pattern for at least clarifying the rough plan for the pleating; I basically used its markers at the front and back edges, and then added some fudging in between to get it to both fit and look how I wanted. I originally tried underlining the fabric with a craft netting to give it more volume, but my smooth fabric didn’t cling to the netting at all so while the netting had big, smooth folds, the fabric just slid over the top. So my folds definitely aren’t as full and thick as in the illustration. (Apparently étamine was a lightweight cotton, loosely-woven, almost mesh like fabric… so I’m not sure how much body it would have had either.) But I think they will do, even if they aren’t quite like what was illustrated.

Arranging the pleats and folds of the upper layer was definitely the longest and most nerve wracking part of this project. Once done, I hand-basted them to the bodice and then carefully hand-stitched from the right side, and then catch-stitched down the seam allowances on the inside. This took forever as I kept having to tackle it in tiny ten minute intervals, but did eventually, and it does make the intricate upper layer very simple to take on and off.

And that’s about that! I’d like to add a big red bow on top of the bustle, and I might just have enough long skinny scraps to add the 4” ruffle the pattern describes to the foundation skirt, if I want to. I’m contemplating some hooks and eyes at the bottom front of the bodice, to keep the various layers all together in the front, since that’s one of the things I like about the original illustration. But on the whole this has been a much bigger project than I had originally envisioned, so I’m happy just to get to wearable!

I’m making you a coat. It’s a shop project so it has to be done in a couple of weeks. So you should really pop by.

I’m making you a coat. It’s a shop project so it has to be done in a couple of weeks. So you should really pop by.

And then I need to bite the bullet about trim. I have a ton of 5/8″ satin ribbon in the right red, some pleated, some not… But what, where, and how much is enough? Or too much. Is it possible to have too much of anything on a Victorian getup? I think we’re straying into “taste” territory again…

And then I need to bite the bullet about trim. I have a ton of 5/8″ satin ribbon in the right red, some pleated, some not… But what, where, and how much is enough? Or too much. Is it possible to have too much of anything on a Victorian getup? I think we’re straying into “taste” territory again…